Mobileye puts lidar on a chip creating Map Intel's Future

It's been a rocky stretch for the chipmaker. But a bright spot was on display at this year's CES.

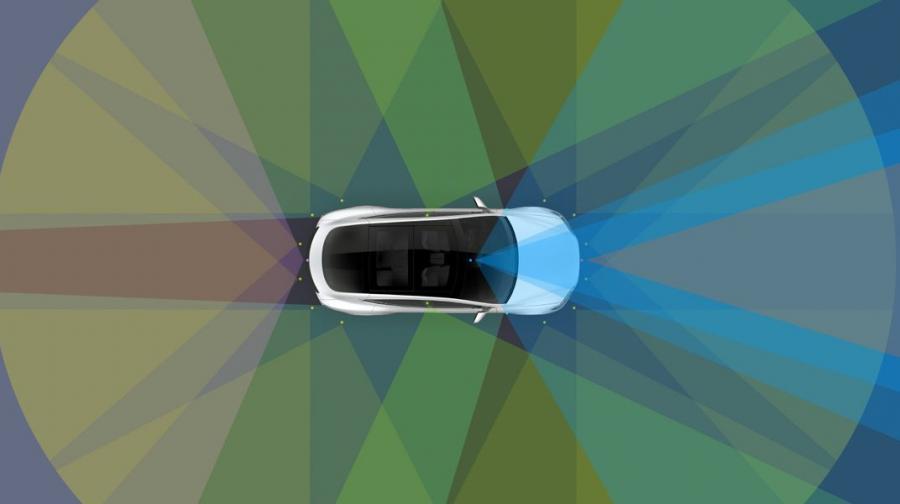

THE RECENT PAST has not been especially kind to Intel. The chip giant has been hamstrung by manufacturing delays, remonstrated by activist investors, and beset by competition from familiar rivals like AMD as well as from Apple, whose M1 processor is an unabashed powerhouse. There have been bright spots as well, though, including one announced today: Mobileye, the self-driving car company that Intel acquired for $15 billion in 2017, has put lidar on a chip.

Mobileye is not alone in its pursuit of shrinking down lidar in both size and cost; companies like Aeva and Voyant Photonics have developed their own systems as well. Mobileye CEO Amnon Shashua doesn’t expect his lidar system-on-a-chip to be fully baked until 2025. But it’s the kind of breakthrough that will help the company retain its tight grip on the assisted driving technology market, with the potential to dramatically drive down the cost of the sensors that will help enable full autonomy. As part of Intel, Mobileye can tap into manufacturing resources few can match, not only to produce the chips on schedule but at scale. More importantly, the lidar SoC is emblematic of Intel’s way forward: looking beyond the CPU.

Chip Shot

Start with the lidar SoC itself, which Shashua announced today during the CES technology trade show. Lidar systems use lasers to determine the location of objects. About the size of a Triscuit, Mobileye’s prototype integrates those lasers onto the chip itself through a process called silicon photonics. And rather than using time-of-flight—which sends out bursts of discrete pulses of light and measures how long it takes that pulse to return to the sensor—Mobileye’s solution relies on so-called frequency modulated continuous wave technology, which instead sends out a constant stream of light. FMCW systems can calculate both the range and velocity of objects, which makes it more effective than time-of-flight.

“You will be able to see hazards on the road from 200 meters away versus 100 meters away,” Shashua says. “The fact that you have velocity data at every point, this 4D measurement also gives you a huge advantage in terms of fidelity of data and what you can do with it. You can do better class terrain, you can get the heading of targets instantaneously.”

Silicon photonics is itself not a new method of manufacturing chips; Intel has previously used the technology in data center transceivers. But lidar is a natural fit, given that it relies on lasers in the first place. It’s certainly an improvement over the bulkier, more costly systems used today.

“The advantage that silicon photonics can bring is a small form factor solution, which can result in a compact size of the device in the car at the end,” says Kiyoul Yang, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University who focuses on photonic hardware. Many companies today use a lidar system based on rotating mirrors, Yang says, which requires the manufacture of discrete, expensive components. “If everything can be integrated in a chip in a small form factor, then everything can be produced with a low cost,” he says.

Again, Mobileye is not the only company banking on FMCW, or lidar chips more broadly. But it does have a distinct advantage in that Intel already has a silicon photonics manufacturing facility up and running in New Mexico. “Being able to build an FMCW lidar requires know-how, but also if you don’t have the special fabs to create the lidar on a chip, it becomes too expensive. It becomes unwieldy,” says Shashua. He expects the cost of each lidar SoC to be in the hundreds of dollars each, orders of magnitude cheaper than what systems cost today.

Even if Mobileye’s production roadmap holds steady, an uncertain regulatory outlook could slow its timeline. Still, it’s making nearer-term progress as well, announcing at CES today that it would expand its autonomous vehicle testing to Detroit, Paris, Tokyo, and Shanghai in 2020. (The locations are strategic; each is near a car manufacturer that Mobileye supplies self-driving technologies for.) And it has used the millions of cars with Mobileye onboard to crowdsource a map of almost 1 billion kilometers of the world’s roads to date, processing 8 million kilometers every single day. For all the attention Tesla gets, Mobileye is by far the market share leader in the autonomous driving space.

That reputation, and Intel’s deep pockets, will help it against smaller competitors in the lidar SoC race. “I’m a big believer that in the auto industry, trustworthiness is a big differentiator,” says Mike Ramsey, an automotive analyst at Gartner. “Can I trust this vendor to deliver on time, to deliver in quality? And Intel has the very important feature of being a very large throat to choke if something goes wrong. Don’t underestimate the value in that.”

Mobileye makes up a small percentage of Intel’s revenue overall. But along with the client computing group—that is, the chips that go into PC and adjacent products—it’s the only segment that grew in the company’s most recent quarter. It’s exactly the kind of new territory that Intel needs to stake out aggressively to avoid another smartphone-style miss.

“If you look long-term, a company like Intel needs to look for new growth domains. It’s not easy to find one. You want to look for a new market that is the size of hundreds of billions of dollars,” says Shashua, as well as one that leverages Intel’s strengths. “Those domains are rare. We are in that domain.”

XPU Marks the Spot

Mobileye’s lidar SoC is the sharpest example of what Intel calls its “XPU” strategy—that is, looking beyond the CPU to computing in all of its many forms. The company launched its first discrete graphics card last fall, has a dominant position in data center processors, and in 2019 acquired AI chipmaker Habana Labs, which a few weeks ago won business from Amazon Web Services to use its accelerators to train deep learning models.

“At our heart we’re a computing company,” says Gregory Bryant, who leads Intel’s client computing group. “We see this world where more and more things need computing, more and more things look like a computer, not just the server or the PC but the automobile, the home, the factory, the hospital. All those things need computing, and need intelligence.”

That broadening out comes at a time when Intel faces more challenges than ever to its traditional business lines. Manufacturing delays have kept it stuck on a 10-nanometer process for fabricating its chips, while competitors have moved on to smaller forms. The company’s chief engineering officer, Murthy Renduchintala, left last summer. And the hedge fund Third Point issued a scorching public letter in late December, calling on Intel to “retain a reputable investment advisor to evaluate strategic alternatives, including whether Intel should remain an integrated device manufacturer and the potential divestment of certain failed acquisitions.”

Click here to read the original!

21.01.2021

21.01.2021

v.dangptb

v.dangptb